Surging global prices of raw materials are one of the most prominent features of the pandemic. Supply shortages, as well as changes in demand, led to strong upward pressures in prices.

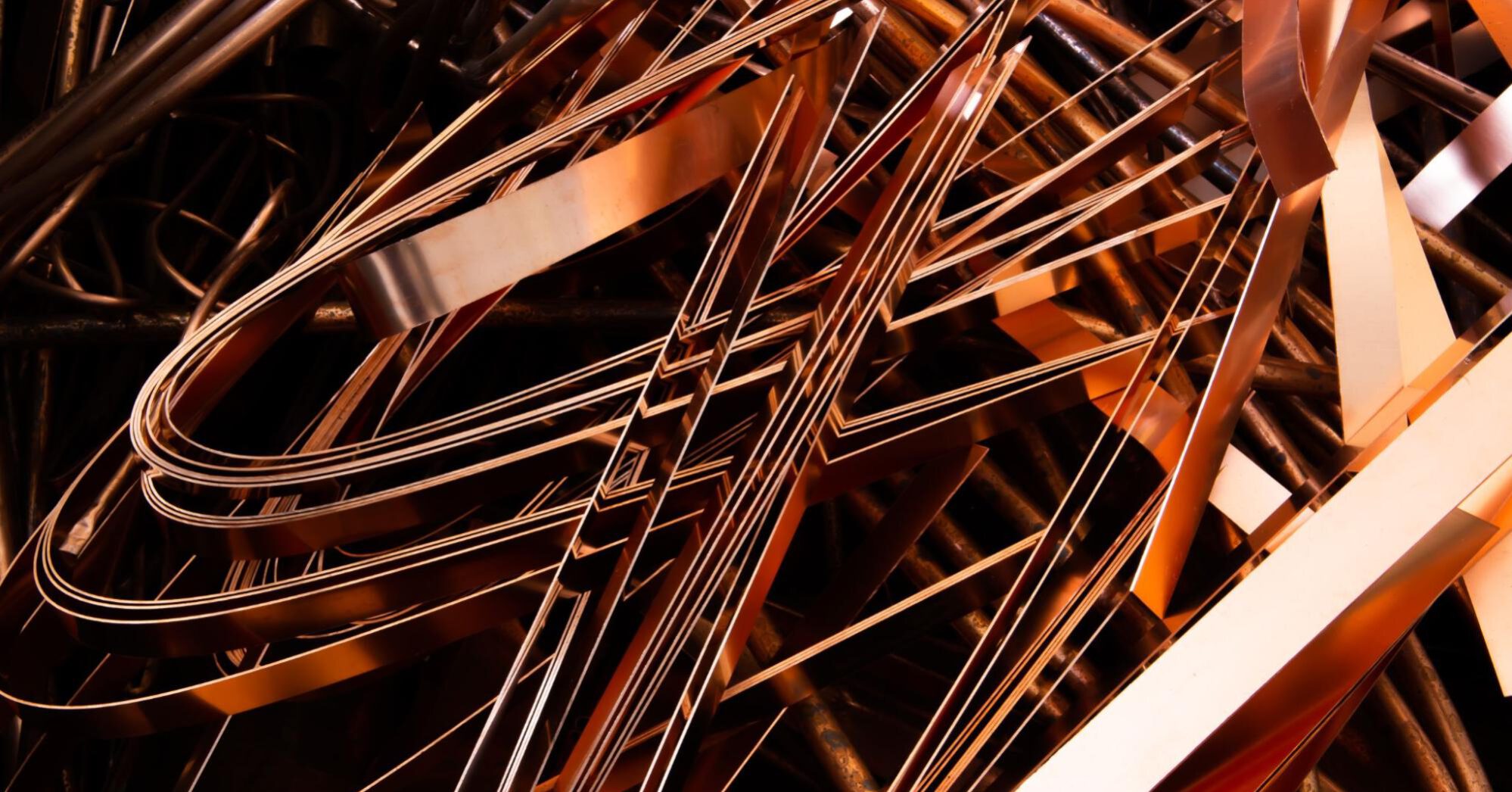

For example, lumber jumped from $300-$400 pre-pandemic to a high of $1544. Just recently, a hot housing market pushed lumber prices back above $1000. On the other hand, the price of copper more than doubled from its pandemic low. An ounce of copper now hit an all-time high of $10,700 per ton in May.

Demand pressures, monetary policy and the accompanying speculation led to a surge in raw material prices. This raises questions on the long-term effects of the price surge. Paradoxically, historical examples are suggesting that the industry could face an entirely unexpected risk down the line.

Pandemic caught producers by surprise

Before the pandemic, commodity prices were on a declining trajectory for almost 10 years. In that environment, many raw material producers and suppliers kept their capacity low. In fact, some even reduced production or shut down entirely.

However, after the emergence of the coronavirus, many suppliers were forced to shut down production. Accordingly, this resulted in a large and sudden reduction in capacity, leading to lower supply.

At the same time, changes in consumer behavior boosted demand for raw materials. All of a sudden, stranded at home, people began thinking about remodeling their houses, apartments, etc. This led to a surge in demand for raw materials used in construction—lumber in particular.

Moreover, the unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus also helped boost demand. It also contributed to the mismatch between supply and demand. Simply put, production was stagnant or lower, while people’s access to money increased. This also put upward pressure on all prices, including those for raw materials.

Supply shortages often come at times of crisis

Periods of raw materials’ supply shortages are not uncommon. Just like now, these periods are generally associated with periods of instability and crisis.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, supply shortages accompanied World War I and World War II. Whereas the present supply shortage was caused by the pandemic, the previous two were caused by global conflicts.

During those periods, instead of pandemic shutdowns, production was reduced due to bombs. Global trade, on the other hand, was not due to countries closing borders to prevent the spread of the virus. Rather, it was due to warfare. The demand was up as well. However, that was a result of the needs of the war industry.

There are more recent examples as well. The 2000s energy crisis saw a boom in oil prices, up to $120 in 2008. There were several causes for the surge, including tensions in the Middle East, worries over peak oil, etc. The surge in prices only made the 2008 credit crunch even worse. Naturally, oil prices collapsed soon, as the world entered the recession.

The interesting fact is that in all three of these cases, supply shortages were followed by a collapse in prices. World War I and II were followed by a raw material boom. Similarly, the 2008 oil shock was followed by a rapid collapse in energy prices.

Prices might swing hard—in the other direction

As mentioned before, commodity prices are high due to low production capacity and excess demand. Both of these factors can be traced to specific factors that came about during the pandemic. However, as the pandemic subsides, and things return back to normal, there is the risk of prices swinging in the other direction.

On the supply side, the end of the pandemic would mean that raw material production and shipping could return to normal capacity. This will mean a higher supply, leading to lower prices. On the other hand, surging prices of raw materials already led some producers and suppliers to increase capacity. Paradoxically, this means that producers may find themselves with more unused capacity after the pandemic.

The same is true for the post-pandemic demand. Once social gatherings become a norm again, people are likely to spend more money on travel, eating out and other experiences. What is more, the money they spend on their living environments might suppress demand for similar improvements in the near future.

That is why the global raw materials industry could risk potential oversupply in 3 to 5 years after the pandemic. This will be a serious challenge for the industry and may have a significant impact on the global economy as a whole.

New risks for the industry

The industry now faces a dilemma. On the one hand, there are pressures to increase capacity in the short term, to reduce the impact of the pandemic. On the other hand, increasing capacity might hurt the industry’s long-term prospects.

Oversupply of raw materials might make large segments of the industry unprofitable. This could lead to layoffs, shutting down of capacity and impact the entire economy. Finding the right balance in the following few years will be crucial for the industry.